What’s been happening in the financial markets?

As we outlined in June, it has been a challenging year for global financial markets. Against a backdrop of high inflation, slowing global growth and a significant change in monetary policy from the world’s major central banks, equity and bond markets have suffered declines amid high volatility.

For much of 2022, asset prices have been influenced by these global headwinds, but in the last couple of months, domestic political events may have also contributed to the volatility.

Certainly in the media, some of these market movements were portrayed as reflecting a loss of economic confidence in the UK. Although that may have been true to an extent, these were not hugely out of line with what was happening in the rest of the world.

In global bond markets, some of the price moves were alarmingly swift, but that reflected the likelihood that interest rates in the UK, US and elsewhere would have to rise further than previously anticipated to curb inflation before it became a permanent feature.

What is a bond?

Bonds are a form of lending to governments, companies or other institutions. Like all forms of borrowing, there is a cost involved. For bonds, the cost is known as the “coupon”, which is a rate of interest payable by the borrower on a regular basis to the bond holder. This coupon is typically fixed (hence the name of the asset class – fixed interest) but the price of the bond will vary depending on demand and changes in the future outlook for interest rates. A bond’s yield is a function of the bond’s coupon and market price (coupon / price = yield), so that too is variable, moving up and down as its price fluctuates. When the price of a bond rises, its yield falls and vice versa.

Recently, bond yields have been rising in the UK, the US and many other parts of the world, because expectations for future interest rates have been increasing as the fight against inflation intensifies. This is a worldwide phenomenon, because the inflationary pressures we are currently experiencing are being felt globally.

What is government borrowing?

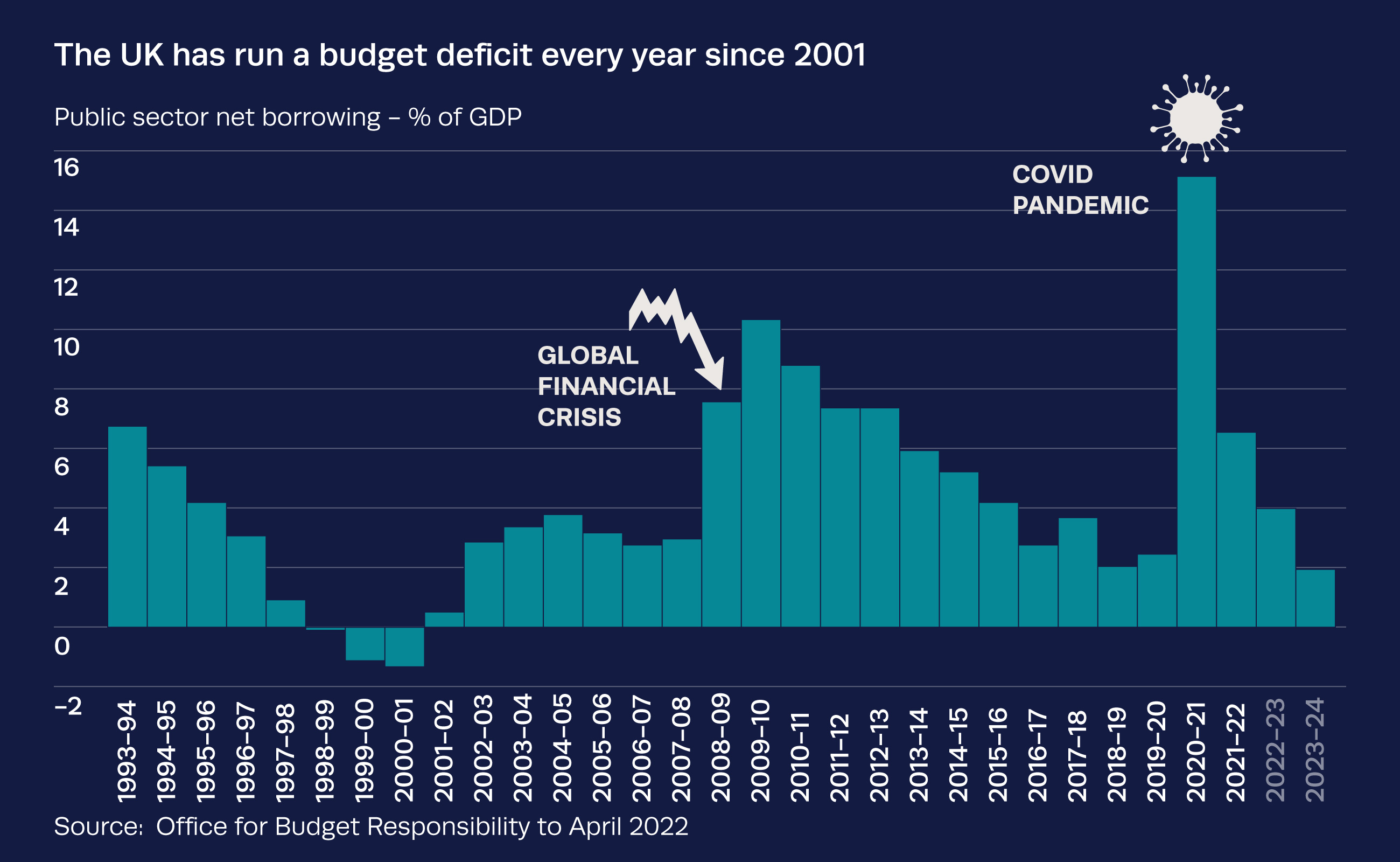

Governments borrow to finance any gap that exists between their income (through tax receipts) and their spending (on public services). Since 2001 UK government spending has exceeded receipts every year, which means that, in aggregate, a substantial amount has needed to be borrowed – the ‘deficit.’ This has been achieved with little difficulty, because there has been an extraordinary amount of demand for bonds from two key sources.

Firstly, defined benefit pension funds have become significant buyers of bonds, having found themselves over-exposed to the equity market in the late 1990s technology bubble. When that bubble burst, these pension funds saw the value of their equity assets collapse, to the extent that there were concerns that, with the recipients of those pensions living longer, they would not be well-enough funded to meet future liabilities. These pension funds have subsequently been consistently advised to “de-risk” through a strategy known as “liability driven investment” or LDI. This basically involves selling equity assets and buying bonds (primarily UK government bonds) and using the income from those bonds to meet future liabilities. Many pension funds also use derivatives as part of their LDI strategy, to manage the balance between their equity assets and their longer-term liabilities.

Secondly, central banks have become major buyers of government bonds. In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, governments stepped in to rescue their banks at considerable financial cost, whilst simultaneously stimulating an economic recovery from the worst recession in living memory. This involved unprecedented amounts of government borrowing, alongside a new monetary policy called “quantitative easing” (QE), through which central banks such as the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve created billions of pounds and dollars with which to buy up this additional supply of government bonds.

These policies have been reintroduced whenever the economy (or stock market) has hit a bump in the road, including during the Covid pandemic, when they were utilised on an unprecedented scale to finance the various emergency measures that were introduced to protect individuals and businesses from the economic impact of lockdown. In total, the Bank of England has bought £875bn worth of government bonds known as Gilts.

In effect, QE has enabled governments to run massive budget deficits for more than a decade, to the extent that the total level of government borrowing outstanding has risen to levels never seen before outside of major wars.

How much is too much government borrowing?

This has always been, quite literally, the trillion-dollar question. Government debt has increased from $100 trillion to $277 trillion since the Global Financial Crisis commenced in 2007. Some economists believe that there is no limit to the amount of debt a government can issue, but “modern monetary theory” as it is known, has never been tested to the ultimate limits.

Historically, financial markets would usually act as a constraint on governments that were fiscally profligate. The term ‘bond vigilantes’ was originally coined in the early 1980s to describe how the bond market could force the hand of central banks or governments, by demanding higher yields (remember this means lower bond prices) if the fiscal boundaries were pushed too far.

For the past two decades, however, there has been little sign of the vigilantes. Inflation has remained subdued, and the successive waves of quantitative easing have deterred any would-be bond vigilantes from demanding higher yields in return for accepting the additional fiscal risk.

That is, perhaps, until now. One could argue that recent events in the Gilt market have provided a serious test to the notion that governments can borrow without limits. However, all of this should be seen in the context of globally higher interest rates and lower economic growth. Both of these forces are negative for global debt, and inflation is the primary culprit. Ultimately, the return of inflation around the world is more likely to lead to the return of the bond vigilantes than the policy initiatives that were proposed by the UK’s new – and as we now know, short-lived – government.

Why has the pound been so weak?

Pound sterling has been weak against the dollar all year but worries about the viability of the government’s new strategy did temporarily exacerbate this weakness. However, although the UK media focused on sterling’s dramatic decline, particularly in the aftermath of the mini-budget, it should be remembered that there are two sides to every currency pair, and the pound’s weakness is a product of dollar strength as well as domestic concerns.

This is because the US has been raising interest rates faster than most other economies, and because the dollar is seen as the ultimate “safe haven” in times of uncertainty. Meanwhile, although the US economic outlook is far from rosy, it is arguably in slightly better shape than the economies of Europe, so there are many reasons why the dollar is strong, and some of them may persist for some time.

What do LDI strategies have to do with all this?

As summarised above, LDI involves pension funds selling equity assets to buy bonds in an effort to match their asset base to their long-term liabilities. Derivatives are often used to help manage an LDI strategy, and whilst these are tools that are used widely in institutional finance, they have two distinct characteristics that can become disadvantages in certain market conditions. Firstly, they can add leverage or gearing to a portfolio. This is ok when markets are calm but can exacerbate a portfolio’s vulnerability to volatile price movements. Secondly, derivatives require collateral to be posted against them, and the amount of collateral required changes with price movements and with the cost of borrowing.

It would appear that some British pension funds were over-reliant on derivatives in managing their LDI strategies. As Gilt yields suddenly moved higher, they became forced sellers of those Gilts because they were required to post more collateral against their derivative positions. In turn, this has weighed even further on the price of those Gilts, forcing Gilt yields still higher and prompting even more selling from the pension funds.

This is similar to some of the price action that contributed to the Global Financial Crisis, and clearly it can become dangerously self-fulfilling. Hence, the Bank of England swiftly stepped in with more QE to calm markets. This effectively gave the pension funds a small window of time in which to reduce their reliance on derivatives, make the changes they needed to their portfolios, and thereby short-circuit the vicious cycle of selling. This appears to have been successful and, coupled with the appointment of a new Chancellor and Prime Minister, order has now been restored to the UK government bond market.

How has my portfolio performed through all of this?

Your portfolio consists of a globally diversified spread of investments across different asset classes. There is no domestic bias, so the volatility recently seen in UK financial markets has not materially impacted your portfolio.

Nevertheless, it is also worth reiterating that much of what has unfolded in UK markets is a function of global dynamics. Inflation is a problem everywhere, interest rates and bond yields are rising everywhere, and all major stock markets have struggled. So, this has not been an easy year for your portfolio, despite its diversification and careful construction.

Some elements of our central investment proposition will have worked in your favour, though. A rising US dollar provides a positive contribution to sterling-based returns, as US assets are worth more – over 20% more in the past year. This has helped to shore up portfolio returns for many. Of course, should sterling start to appreciate again, the opposite would be true.

Meanwhile, the value bias within portfolios has also helped deliver a relative benefit, because in general, stocks (and indeed whole markets) that represents good value haven’t fallen as far as those which are more expensive. Indeed, some of them have risen, despite the widespread market declines.

Overall, therefore, it has been a challenging year for all investors, but many of the hallmarks of the Cavendish investment philosophy will have worked in your favour from a relative perspective.

What should I do?

Media headlines in the UK haven’t made for comfortable reading of late. Although some of these stories may make us feel like we need to act, this is almost certainly the last thing we should be doing. In essence, no-one really knows how this will play out, but investors who own globally diversified portfolios of equities and higher-quality shorter-dated bonds should be well-positioned to weather what lies ahead.

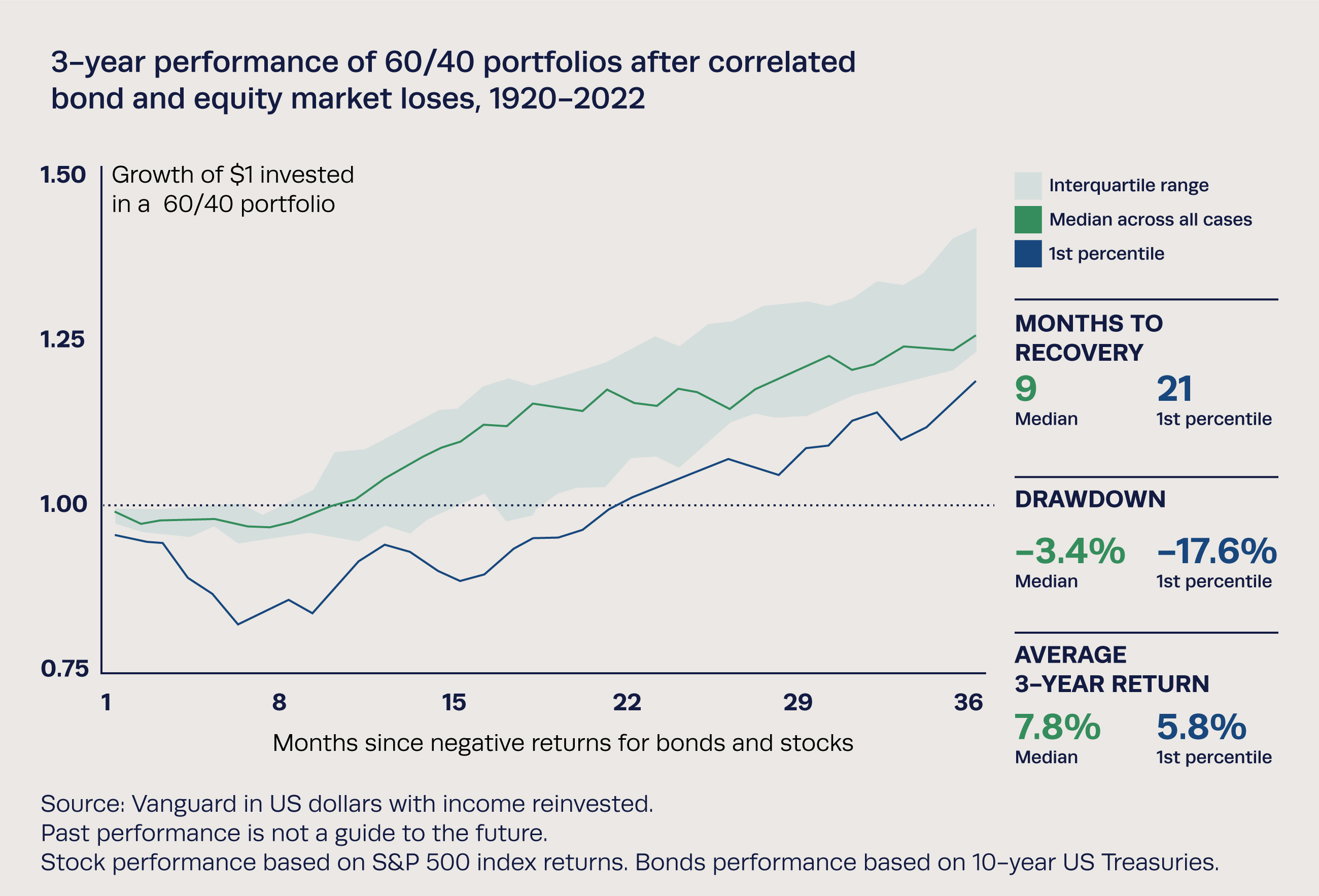

Many commentators refer to the classic blend of equities and bonds as the 60 / 40 portfolio (60% equities / 40% bonds). In reality, few clients will own that precise blend of assets, but it is a useful theoretical construct for illustrating the diversification benefit of owning both return-seeking and defensive assets.

The 60 / 40 portfolio has clearly struggled this year, with both of those key components suffering widespread price falls. But, although it is unusual to see equities and bonds decline simultaneously, it is not unheard of. The chart below is the product of an analysis of all previous occasions in which bond and equity markets saw correlated losses, and it tracks the length of time it takes for those losses to be recouped.

The good news is that, on average, the 60 / 40 portfolio has taken just nine months to recover its losses. It has then gone on to deliver a 7.8% annualised return over the three-year period from the point at which those losses started. Even in the worst case historically (as represented by the 1st percentile line), it has taken 21 months for the portfolio to recover, and three-year returns are still positive at 5.8% per annum.

Perhaps the current situation turns out to be a new worst case, but the intellectual rigour behind the concepts of sensible diversification, long-term thinking and keeping investment costs to a minimum should remain powerful influences on our behaviour. This approach advocates waiting patiently for the recovery that has more often than not arrived in the past. History is on our side – and so is the long-term relationship between risk and return.