Tariffs – what are they and why do they matter?

With the re-election of President Trump, trade tariffs have once again taken centre stage in economic and market debate, contributing to widespread volatility in global equity markets. Such conditions can be unsettling and, even with the recent announcements, much remains uncertain over how far America’s new trade policy will extend, how high tariff barriers may rise and for how long they may remain a feature of US policy.

Furthermore, many nations that have had tariffs announced, or imposed upon them have immediately reciprocated, which has historically been a typical, and rational, response. Thus, it is hard at this stage to predict how far the tariff trend will extend. Is President Trump primarily using the threat of tariffs as a bargaining chip to pressure trade partners into concessions? Or is he committed to using trade barriers as a long-term weapon, in pursuit of his “America First” agenda? Will he really be able to keep these policies in force if his ‘popularity’ with US consumers and voters is badly impacted?

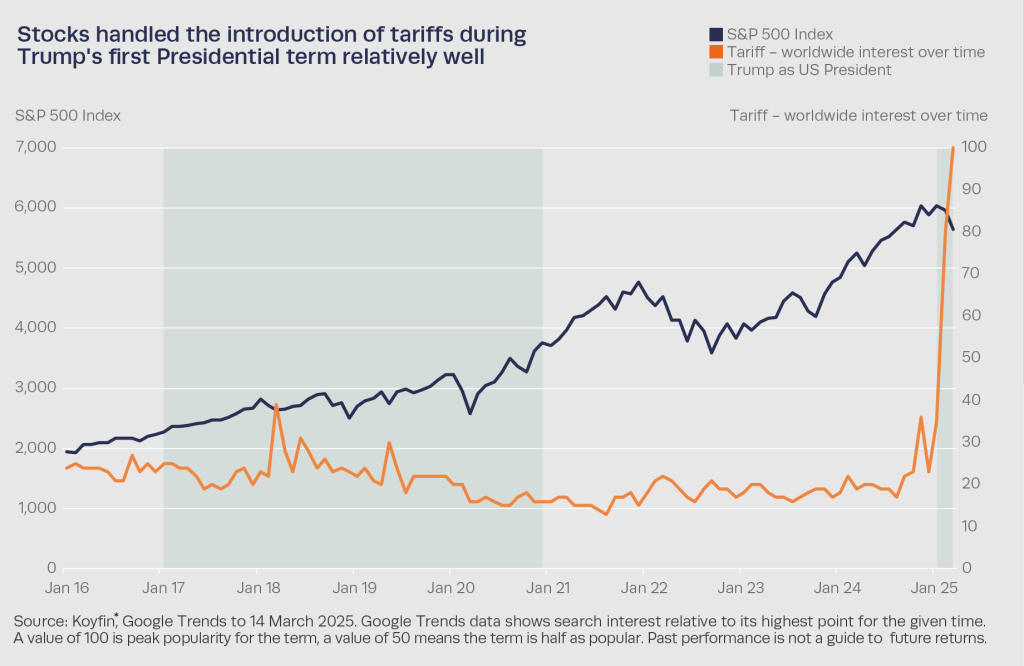

At times like these, it can be helpful to take a step back. Tariffs have been a feature of economic policy throughout most of history, and while recent decades have seen a shift towards globalisation and ‘free trade,’ the chart below shows that financial markets were able to look through the selective reintroduction of tariffs in 2018, during President Trump’s first term.

Lessons from history

For much of history, tariffs have been a central tool of economic policy, used both to generate government revenue and to shield domestic industries from foreign competition. The word itself hints at its long lineage, deriving from the Arabic ta‘rīfah, meaning a notification of fees. This etymology reflects how trade and taxation have been interwoven throughout civilisations, from the ancient trade routes of the Silk Road to the industrial age.

At its core, a tariff is a simple tax imposed on imported goods, making them more expensive relative to domestically produced alternatives. Once upon a time, they were a very important source of government revenue – in America before the Civil War, around 90% of the fiscal purse came from tariffs.

More recently, however, there has been a progressive move towards trade liberalisation, underpinned by the establishment of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947, which sought to reduce trade barriers and promote economic cooperation in the aftermath of World War II.

As trade barriers fell, global supply chains expanded, benefiting businesses and consumers through lower costs and greater access to goods. Increased globalisation has also arguably contributed to a relatively stable geopolitical backdrop for much of the last 80 years.

Nevertheless, the past decade has seen growing scepticism about globalisation’s downsides. Many jobs have been displaced as manufacturing has moved to parts of the world that offer cheaper labour and perhaps less regulation. Meanwhile, trade liberalisation has often gone hand-in-hand with increased labour mobility, which has tended to undermine western workers still further.

Populist politicians have capitalised on these grievances, bringing protectionist measures back into mainstream economic policy. What was once considered an outdated relic of economic history has now re-emerged as a controversial tool of modern statecraft, with implications for financial markets and investors that are not yet clear.

Economic impacts

Tariffs are often framed as a tool for economic protection, but their effects are complex. They can raise costs for businesses reliant on imported materials, leading to higher consumer prices and inflationary pressures. In turn, this can influence central banks’ decisions on interest rates.

They are also expected to have a negative impact on global economic growth, with leading economists warning that substantial tariff hikes could decrease global output by 1-2% over the next couple of years.

Much depends on how far the US administration is prepared to push its protectionist policies, however. Meanwhile, the globally-integrated nature of modern supply chains means that the impact of tariffs can be hard to measure precisely, with unintended consequences potentially emerging in unexpected places.

For example, the US automotive industry has strongly opposed the recent proposal to introduce tariffs against Mexico and Canada, warning they will raise costs, disrupt global supply chains and threaten domestic jobs. Similarly, several US pharmaceutical companies have significant manufacturing operations in Ireland – these could face disruption if tariffs are imposed on their imports, potentially affecting their supply chains and cost structures.

Geopolitical impacts

Beyond economics, tariffs have become a key instrument in geopolitical strategy, and many commentators view America’s tariff policies as reflective of a shift away from the “soft diplomacy” that has characterised much of the post-Cold War order, towards a more confrontational, “hard diplomacy” stance towards friend and foe alike. Tariffs have increasingly been used as a tool for geopolitical leverage, contributing to rising tensions, not only with China but also among key North American and European trade partners.

Market impacts

For investors, the renewed focus on tariffs has been an obvious source of concern. The reality is that much remains unknown about the full impact of President Trump’s broad based tariff policies, and their potential economic consequences in the medium term. This uncertainty is currently creating unease in markets, but we do have some evidence from prior actions on tariffs, albeit in a more limited form.

In early 2018, tariffs were introduced on imports from China, sparking uncertainty and volatility. This is evident in the chart above, with the orange line showing the level of global interest in the search term ‘tariff’ suddenly spiking higher. While markets reacted negatively at first, they did recover their poise in time. Clearly, the current interest in tariffs is much higher, no doubt due to the levels being proposed, and the apparent emphasis of the politics and optics taking precedence over financial markets, ‘rational’ trade policy and global growth.

The key for investors is to remember that markets can over-react to short-term uncertainty, whatever it’s source. When this happens, it is important to remain disciplined, well-diversified and focused on the long term.

Conclusion – stay focused in uncertain times

Inevitably, investing always involves noise and getting used to uncertainty, but the sources of this change over time. At the moment, the focus is very much on tariffs, but that won’t always be the case. We cannot predict how long concerns over trade wars will influence market sentiment, nor can we know what will dominate the market narrative next. But it is worth remembering that even the four-year term of the US Presidential cycle is quite short in the context of a long-term investment journey.

In the meantime, the Cavendish investment approach remains focused on diversification, discipline and ensuring that portfolios are ultimately built to weather different economic environments. Market setbacks can be uncomfortable, but history shows that reacting to short-term movements is rarely beneficial for long-term investors. Headlines change over time, but the principles of sound investing do not.