Interview with Revd John Horton

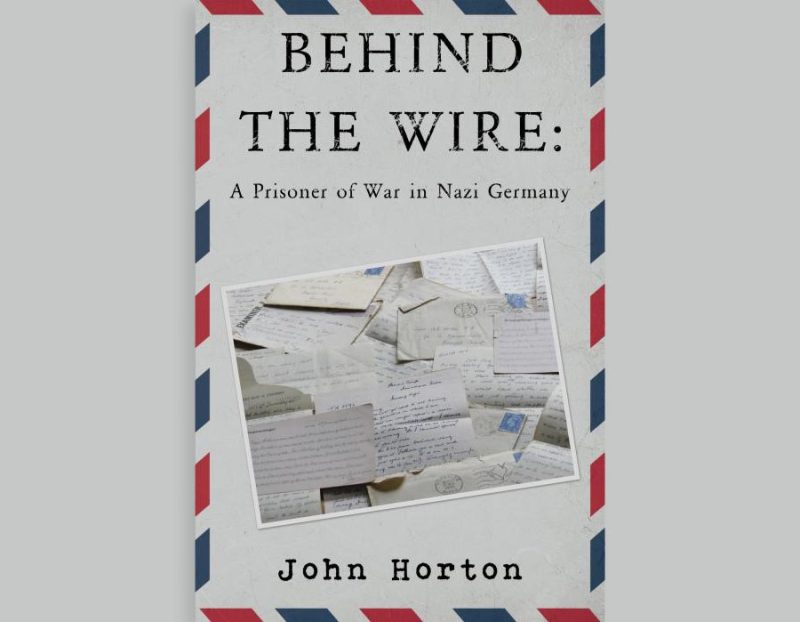

John Horton spent much of his working life in Africa involved with agriculture and development before being ordained into the Church of England. John has used his retirement to turn his parents’ wartime letters into a book ‘Behind the wire: a Prisoner of War in Nazi Germany’.

-

The book publishes the letters exchanged largely between my mother and father between 1940 and autumn 1945 when he was a prisoner of war in Germany. We knew the letters existed but had never seen them until my mother died and we found a big box in the loft.

Alan and Peggy Horton were married in 1940. Within a few weeks Alan was on a two-month voyage from Glasgow to Egypt. From there, my father and his men were shipped to Crete where they suffered a catastrophic defeat; many on both sides were killed. Along with countless others, he was taken by cattle truck to Germany, and imprisoned until hostilities ceased. There were thirty seven to a truck and all had dysentery. The train would stop for just five minutes a day.

The book recounts the story of life in wartime Britain, highlighting the pain and separation of war but enlivened by love and hope for a lonely young bride. The letters depict the frustrations and boredom for fighting men, forced to sit idly as the war raged on.

There are also letters from a mother looking for her son after the Battle of Crete, the letter from the Colonel of the Regiment to say they had lost my father and thought he was probably a prisoner of war but weren’t sure and letters to the Red Cross from my mother trying to find out where her new husband was.

-

Yes, the correspondence has been described by the Imperial War Museum as one of the most complete sets of letters they have ever seen written between husband and wife. The Museum would like the letters in their entirety rather than have them on loan which is a shame as we would like to keep them in the family.

The issue is storing them safely which museums know how to do. The letters are written on very thin airmail paper and my mother’s writing was always difficult to read. Some 80 years on it is even harder to decipher. My father’s handwriting is easier but he was limited to four postcards a month and he also needed to write to his own mother and family so he wrote less often and they were shorter letters.

-

They were allowed pens, paper and postage but all letters were censored. Even on the original voyage from Glasgow to Egypt via the Cape of Good Hope one of the jobs my father was given was to censor the men’s letters to avoid sensitive information getting out. He hated doing it.

Letters also took a long time to come back and forth. I showed them to a group of school children and I asked how quickly they expected a reply to a text. They said around five seconds!

None of the letters arrived quicker than two weeks and most took between two-four months. Father wrote to say that he was alive and a prisoner of war in June 1941 but that didn’t reach my mother until a few months later. In one of the letters, my mother wrote to say that she had been in hospital with appendicitis. Father’s reply came months later to say he knew she was alright but didn’t know she’d even been ill. The letters in between were seriously delayed.

-

Little bits we had heard before but, in some ways, I struggled with the idea of reading them as they are essentially love letters between two people. However, you do learn about the realities of war and that is something which is remarkably relevant. We have war in Europe now and prisoners of war being taken by both sides. Relevant today as much as those days.

Throughout the letters there is an incredible amount of hope. Each year they thought it would be over by the end of the year or by the end of the season. Father was in prison for four years. There were at times some feelings of resentment. His brother had a successful career in the Marines which he would love to have done. Sadly, he was locked up and couldn’t do anything to help.

Nevertheless, he didn’t waste the years in prison. He studied for the Institute of Bankers’ exams plus the Institute of Chartered Secretaries and a degree in economics. The last two accreditations he never received because they think the plane carrying the exam papers was shot down on the way home. He also played a lot of sport and shared a vegetable garden to try to improve their food allowances.

-

Like many men of his generation returning from war, my father never spoke about his experiences. If he was asked to give a talk on the subject, you would not learn much about the war because it would simply be a collection of silly stories and the harder facts would be glossed over.

We have learnt more from the letters and from other materials. The letters don’t say the really bad things because father didn’t want to worry mother more. They were also censored but she sometimes got hold of information from other prisoners’ wives.

There was of course a happy ending as he came home and they continued married life.

In fact, he got home a little earlier than he should have done. At the end of the war, the prisoners from his camp at Eichstätt were lined up at 5am on the road outside to march south to join General Patton’s army. They saw an American plane go overhead and clapped and cheered thinking the Americans were there to relieve them. A few minutes’ later, the plane came back with some others and shot the whole column up. They killed nine or ten and injured something like 46 others. Father was injured – he had shrapnel in his leg. So he got home earlier but not for the best of reasons. As a small boy, I asked what happened to the shrapnel and he told me that it went through the head of the next person.

We discovered by listening to an audiobook about Colditz that the prisoners there had heard what had happened at my father’s camp. They gathered all the material and cloth they could find and cobbled it together to make their national flags. When the time came to leave the camp, they hung them outside the windows of the prison as the Americans arrived to prevent friendly fire.

-

I heard Book of the Week on Radio 4 back in 2014 which was marking the start of the First World War. They were reading letters between a husband and wife, and I thought ours might be interesting to read too.

I first started looking into it in 2005 when I was training for ordination in the Church of England and had some time to work on them. I tried to get them published and repeatedly got rejected. However, one publisher wrote back advising that I leave out the background material and let the letters speak for themselves.

By then, I had just been ordained and for the next 12 years was too busy working. In the first lockdown I had just retired so got them out and had a chance to focus on them. It probably took six to seven months to compile the letters but then took a lot longer to proofread and produce it.

In fact, I think it is almost harder to get the work promoted than writing it!Behind the wire: a Prisoner of War in Nazi Germany is available to buy at Amazon, Waterstones or Pegasus Publishers.